Conservation Story 14: Learnings from Over 100 Tiger Conservation Areas

Conservation Story 14: Learnings from Over 100 Tiger Conservation Areas

19 Jan 2021

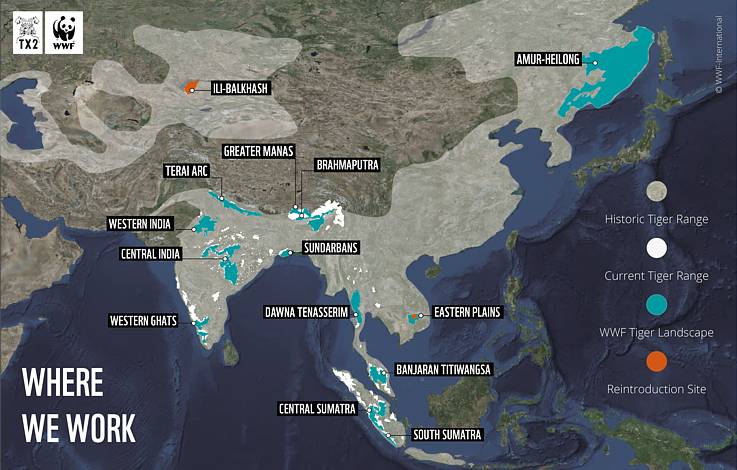

Over the last century, the global tiger population dwindled to less than a tenth of its former size with just 3,200 in 2010. Tigers are no longer found on the islands of Bali and Java in Indonesia or around the Caspian Sea region and have become extinct in Singapore and Hong Kong. There is also no evidence of breeding populations in Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Viet Nam. With a few remaining pockets of sanctuary around Asia, it is our priority to ensure that these areas receive the support they need so tigers can continue to recover and thrive.

Launched in 2013, CATS – which stands for Conservation Assured Tiger Standards is an accreditation system that sets best practices and standards within Tiger Conservation Areas, as well as benchmarking_progress. It is within these areas that the recovery of tigers holds the most hope and where we hope to learn more about protecting this magnificent species.

Recently published in IUCN’s Parks Journal, the study covers the results of the survey conducted in 2018 across 111 Tiger Conservation Areas in 11 Tiger Range Countries and is considered as the largest tiger management study to date. Here are some of the key learnings that we should be focusing on to achieve our goals.

1. 35% of the world’s Tiger Conservation Areas are at risk of serious declines in their tiger populations.

Despite a welcome increase in attention paid to tiger conservation and tangible progress we have recorded, TCAs are continuously threatened by poaching and habitat degradation. To maximise our chances of reaching the TX2 goal – to double the number of wild tigers by 2022, increased action and investments in these areas is needed.

2. Southeast Asia’s Tiger Conservation Areas are struggling with inadequate funding.

Only 35% of TCAs in Southeast Asia are on the way to being sustainable, with additional revenue streams maximised and linked to management priorities. This compares to 86% of TCAs outside of Southeast Asia.

The region is still considered to hold huge potential for tiger recovery in spite of severe and ongoing threats from illegal hunting and snaring. Effective management and investment in areas where tigers are still found and the protection of interconnected habitat could provide hope for the big cats (with progress seen in Thailand).

3. Human wildlife conflict measures must be stepped up.

Fewer than half of TCAs (46%) in South Asia, Russia, and China have implemented effective management strategies for human wildlife conflict. Only two TCAs in Southeast Asia have such systems initiated and another eight have systems under development.

4. Communities must be at the centre of tiger conservation.

Only 53% of TCAs reported that they involve communities in applicable areas of site management and only 30% of TCAs have involved stakeholders in management planning. It is necessary to have people at the centre of tiger conservation and WWF will continue to work closely with its conservation partners to listen, learn and act to make this happen.

What does this tell us?

Global tiger populations are slowly increasing, but their future is by no means secure and the successes are not being seen across the tiger range. The recent findings have shown us the impacts we can make with the support and commitment of all parties involved. For example, in the last few years, we recorded a significant reduction in snare encounters in Belum-Temengor in Malaysia where we have stepped up patrolling in partnership with indigenous communities. We now need to redouble our efforts expand our impact while continuing to put people at the centre of tiger conservation. Below is a short summary of our action plan:

- Many Tiger Conservation Areas urgently need increased funding and policy support from their own governments, as well as targeted support from donors, NGOs, and others to aid basic capacity building and gain greater impact. We are lobbying governments in the region to invest more in key natural areas to protect not just the species but also ourselves by preventing further degradation of our planet.

- In other cases, TCAs need specific support, particularly in terms of policies and training in the area of stakeholder relations and enforcement to manage the sites effectively. Planning for conservation must also include the voices of local communities and indigenous people if it is to be successful and sustainable.

- Protected areas continued use of CAITS to track improvements and changes in management, will enable more effective use of resources and allow for targeted and timely interventions. A comparative study every two years will also be conducted to measure progress.

The year 2020 has reminded us that our relationship with nature is under strain and that we need to protect nature in order to protect ourselves. Large carnivore such as tiger covers a huge range, that is why protecting them means protecting countless other species, forests, and ecosystems upon which millions of people including us depend. If tigers are thriving in a natural landscape it means the entire ecosystem is functioning – tigers are the ultimate indicator of a healthy forest or grassland.